- Home

- Eric Dinerstein

A Circle of Elephants Page 2

A Circle of Elephants Read online

Page 2

The men murmured in approval. My father was not only Subba-sahib, the leader of the stable, he was also a shaman, a spirit doctor, so we did little without seeking Ban Devi’s blessing. Subba-sahib did not linger on the earthquake. “We have much work to do for the arrival of our new elephants. The day they come will mark the moment we truly become a royal breeding center and nursery for the king’s elephants. Let us show our gratitude by attending to our future.”

Everyone nodded and grew calmer. I could see why my father is Subba-sahib. He never panics.

“Nandu, I cannot wait to drive the new elephants,” Dilly whispered to me. We were standing at the back of the group with Rita.

“You cannot ride them, Dilly,” Rita said. “They need to be free from work to nurse their newborns.”

Dilly pretended to look annoyed at his sister, who was three years younger than him. Rita was fond of telling us what was right and wrong. I did not mind half as much as Dilly did. Rita was rather an expert about mothering wildlife. She already cared for the two orphaned rhino calves in our camp as if she were a trained biologist. Father Autry, my teacher and a great biologist himself, had said so. I was sure Subba-sahib would assign Rita to help the drivers look after the youngest elephant calves, too. Dilly would have to get used to her authority.

“Now,” my father continued, “we shall make the New Year’s celebration stretch for several more days while we prepare for the calves and their mothers.”

The drivers cheered and whistled. Rita joined in with a whoop. We Nepalis may be superstitious, but we are also brilliant at making a holiday out of any turn of events. People from other countries could take a lesson from us on this point.

His talk finished, my father found me and grasped my shoulder with his one hand. He lost his other arm to a tiger many years ago. He looked into my eyes. “You are not hurt, Nandu?”

“No,” I said. “Hira Prashad took me to safety.”

He nodded as if this was to be expected. My father has great faith in animals, especially elephants. I wanted to tell him right away about the wild elephant, but then I thought, better to wait until after dinner, when we were alone. He could explain to me what happened like no one else.

We sat in a circle around the campfire with the older drivers sipping tea. Some of the chairs around the fire had been salvaged from a school. They had wooden arms that were perfect for resting one’s head, if you were tired enough, which is what I did while I waited for the talking to end.

After all of the drivers had drifted off to bed, my father and I were finally alone.

“Subba-sahib,” I began. “Something incredible happened today.”

“Something more incredible than an earthquake, Nandu?”

“Yes. I think so. I was standing on the edge of Lalmati, watching two gharial through my binoculars, when Hira Prashad came up behind me, wrapped his truck around me, and pulled me away from the edge. Within a minute, the earthquake began, and the place where we were standing broke off and slid a hundred feet down. I would have died.”

My father held my gaze with his dark brown eyes. They sparkled like gold in the light of the fire. Then he spoke. “You must take me to the spot tomorrow. We will offer our thanks to Ban Devi.”

“And we must thank Devi Kali, too,” I murmured.

“Why is that, Nandu?”

“Nothing. I will tell you tomorrow.”

My father is not the type to hug, but as I stood, he stood, too, and wrapped his one good arm around me and held me to his chest. I am a copper-skinned boy from Tibet, the land of snow north of the great Himalayas. My father is a dark-skinned Tharu from the vast steamy jungles of the plains at the mountains’ base. Our tribes rarely meet, let alone become family, but fate brought us together the day my father found me alone in the jungle, guarded by dhole. Now we are father and son, blood tie or no blood tie. Just the way Devi Kali, the elephant who raised me in the stable, was my mother. She is no longer here to hug me with her trunk, but my father is, and his one-armed hug, to me, is the best feeling in the world.

y father and I left the stable at dawn without saying a word to the other drivers. He wore his canvas bag around his waist, the one he takes to his place of shaman worship in the jungle, where he prays to Ban Devi for the well-being of our elephants and their drivers.

Subba-sahib believes that all living things have souls separate from their bodies, souls that are at one with the great force of nature that is Ban Devi. To him it is always urgent to pray to Ban Devi. In our religion, we believe that nature, animals, humans, and the earth itself all try to live in balance. Part of keeping that harmony is to acknowledge the power of the spiritual world—especially after surviving danger or illness.

Hira Prashad stopped to drink in what was left of the Belgadi River that flows past our camp. My father and I waited while he lowered his trunk and sucked in gallons of water before tipping back his head and releasing the gusher into his mouth. Five times he repeated this to quench his deep thirst.

“Have you ever seen the Belgadi this low, Subba-sahib?” I asked.

“Not in thirty years,” my father replied quietly.

The drought was not as apparent in the flow of the Great Sand Bar River, where I had spotted the gharial yesterday, because its source is the snow of the Himalayas. But the Belgadi is a tributary, and relies on rain to replenish it. It was mid-April, not even the height of the hot and dry season, yet the Belgadi was already reduced to a foot of water trickling down to India. In the summer monsoon, the river is so high that our elephants can barely swim across it.

“What is it, Subba-sahib?” Away from the other drivers, when we were all alone, I sometimes called him father. But the deep look in his eyes told me I should call him Shaman.

“Nandu, I had a vision last week. I saw that this drought will not end soon. There will be no monsoon this year.”

As if to join in our conversation, a hawk cuckoo started its shriek, which grows louder and louder with every cry. In the hot weather, it sings all day. The British who occupied India called it the brain-fever bird. The men could not stand the heat, and the constant racket from the hawk cuckoo drove some officers mad.

“Maybe the male sings extra loud and long during a drought,” I said.

“There may be truth to that, Nandu,” my father replied. “The farmers must see rain in a few weeks or there will be a poor rice harvest. The animals will start to suffer, too, without water. And the fruit on the trees will dry up.”

The signs of drought were everywhere in the jungle. Green leaves, only recently flushed, drooped to keep the sun off their surface. They seemed to whisper as we went by, we are so thirsty, we are so thirsty. Even the flowers fell off the crape myrtle trees like a white rain of dry, delicate petals.

When we reached the Lalmati cliffs, Hira Prashad stopped well back from the jagged edge. The red soil and rock made the sheared edge look like a deep wound in the earth. I guess, in a way, it was.

My father coughed. I could see he was taking deep breaths to keep his emotions from overtaking him. This almost never happens. I did not know if he was feeling awe at the power of nature and Ban Devi, or if he was imagining what would have happened to me if Hira Prashad had not been there.

Hira Prashad let out several deep rumbles. I looked at my father, who nodded, as if Hira Prashad had spoken to him. I do not have the skills of my father. And I am sure that Hira Prashad understands me much more than I understand him.

“Did Hira Prashad tell you about the wild elephant across the river?” I asked.

My father looked at me and shook his head.

“Subba-sahib, there was a female with a calf across the river. Over there.” I pointed to the spot where they stood, just behind the blur of the heat rising off the sandbars. “This was not an illusion, I swear to you. The female lifted her trunk. She trumpeted and moved her head. Like she was warning us.”

“Nandu,” Subba-sahib said. “I think the elephants were confirming what they eac

h felt. Elephants can sense beyond the reach of our own abilities, you know. Not just where to cross a flooding river or how to avoid a patch of quicksand. Elephants notice events before they happen. That is how Hira Prashad saved you. He knew what was to come.”

“They were talking about the earthquake?”

“Yes, I believe so.”

“That calf she had with her,” I said. “I remembered the story about elephants from our stable being reborn in the wild across the Great Sand Bar River. Subba-sahib, I think that young calf was Devi Kali trying to protect us, her sons.”

I had never spoken to my father of Devi Kali as my mother and Hira Prashad as my brother. But he nodded, knowing this to be the truth. “No doubt you are right, Nandu. I do not think the spirit of Devi Kali would travel outside the Borderlands, especially as long as you are here.”

It had not occurred to me before, but I wondered then why Devi Kali would choose to be born wild. For the first time, I questioned if she had enjoyed her life in our stable. My heart grew heavy. I had always believed my fate at the stable was the same as the elephants’ fate. That we had been lucky. Maybe the luck was mine, but for the elephants, their fate was different.

My father and I climbed down from Hira Prashad and let him graze. It was time for my father to perform his ritual of gratitude. He chanted and bowed and brought his palms together in the namaste gesture. He lit incense and sang words I did not recognize. I usually find Father’s rituals strange. In fact, I usually look forward to them being over, but this time I closed my eyes and added my own thoughts and gratitude to Ban Devi for giving me a spiritual elephant family and a shaman for a father.

When my father was finished, Hira Prashad walked over to us, knowing it was time to leave. I hugged my elephant’s trunk and began to tremble. I whispered in his ear, “Hira Prashad, I will always protect you like you protected me.” Hira Prashad bobbed his head and grumbled. He understood. My father and I climbed onto his back and headed to the stable.

“Let us return by the riverbed,” my father said. “In this heat, Hira Prashad will need to drink even more before we head through the jungle.”

I steered Hira Prashad gently with my toes behind his jowls, and he moved effortlessly down the trail from the cliff edge leading to the river. We headed south along the Great Sand Bar River for five miles. Hira Prashad stopped to drink twice. Near the edge of the riverbank, we came upon a man with a long black beard and his son huddled around a small fire. They wore plaid lungis, the wraparound sarongs of Indian fishermen. The boy crouched with his back toward us, coaxing the coals into flame. Above the fire was a drying rack skewered with small fish. I waved to the older man. He stared back at us like he had never seen a tusker.

I am used to people looking at Hira Prashad. My father says our bull has the longest tusks of any male elephant in Nepal. The boy stood up and stared, too. He had dark features and a narrow face; he looked about my age but was very thin, with bird bones. I have the broad body of a Tibetan and the thick muscles of an elephant driver.

I greeted them in Hindi—Ram Ram!—and asked how the fishing was. They said nothing and fixed their gaze on us and my elephant’s tusks. It was unusual for them to ignore our greetings. That is when I noticed their shoes: blue canvas sneakers with white laces. Not many in our village wore shoes.

Once Hira Prashad finished drinking, we turned from the bank and headed toward the vast grassland between the Great Sand Bar River and the Belgadi.

“Subba-sahib, who were they?”

“I have not seen them before, Nandu.”

“Did you notice their shoes?”

“Yes, I do not think they are fishermen. Our fishermen would never ruin shoes going in and out of the water all day.” My father chuckled, as he often finds people foolish. He prefers elephants. Like me.

Because my father did not seem concerned, I dropped the subject of their shoes. This fact bothered me, but perhaps I was jealous because I had none.

Up ahead we saw a familiar friend standing proud in the middle of the grassland. The massive black horn of our jungle’s enormous male rhino gleamed in the sun. His horn was nearly one and a half feet long. A pair of jungle mynahs were perched on his back.

“Good morning, Pradhan!” I said.

Pradhan swiveled his ears, first one, then the other, at the sound of my voice. Or maybe he heard Hira Prashad’s rumble. Pradhan means mayor in our language, and this male rhino, the largest in the Borderlands, had been here since I learned to ride an elephant.

Pradhan was the first rhino I could name by sight. I was very attached to him, but under no illusion that he felt the same way about me. When I was a young stable hand, not even a mahout, I went out to cut grass for the elephants. The drivers dropped me off and left to graze the elephants nearby. No one saw Pradhan in the tall grass.

I was alone when the old male rhino came out of the grass and snorted at me. The drivers sitting on the backs of their elephants stood up and shouted, “Run, Nandu, run!” But it was too late. I could never outrun a rhino. I covered my head and prepared to be trampled and gored.

Pradhan lowered his head and grabbed a wild cane with his upper lip. He had no interest in crushing a naïve stable boy. I was no rival to him. The mayor did not need to prove his strength to me. We both knew that. Ever since that day, Pradhan was family to me, too.

“How old is Pradhan, Subba-sahib?”

“He is as old as I am, I suppose. Maybe a bit younger, with a few less wrinkles,” he said, laughing. My father was at least fifty years old, but like most Tharu, he does not know his age exactly. Age is not a detail that matters to the Tharu.

Pradhan’s skin looked like armor specially crafted for rhinos. He gave us a good, long look, then went back to ripping up the grass blades with his curved upper lip. Pradhan knew us well from grazing our elephants here during the day while we cut grass, and he was used to Hira Prashad. As long as we did not make any sudden moves, we could approach within a few feet of him.

“Subba-sahib, the king of all elephants in Nepal and the king of all rhinos are very trusting.”

“Yes, they are calm. They pose no danger to each other.”

A bigger threat to Pradhan were the other male rhinos who often challenged him to take over the top spot. Pradhan was blind in one eye and walked with a slight limp, but he held his own in battles. Just to let us know he was still king, Pradhan snorted loudly.

I turned and looked at my father. “Subba-sahib, do you think that Hira Prashad has the largest tusks of any elephant in Nepal? Wild or living in a stable?”

“I do. Ramji says he has heard of a wild male with even bigger tusks that roams the Kailali jungle on the other side of the Great Sand Bar River. But we know Ramji drinks too much and tells tales.”

“Maybe there is an elephant with bigger tusks in Nepal, but none braver than our Hira Prashad!” I said, loud enough for my tusker to hear. He thumped his trunk on the ground, a thing he does when he is excited.

The sun was higher in the sky and the air was unbearably hot. If only it would rain. All the birds had stopped singing, except for the brain-fever bird still shrieking its song from the treetops. A half hour later, thirsty and tired, we were happy to see the smoke from burning elephant dung rising above our elephant stable. The tall evergreen mango trees that encircled camp made it look like an oasis. I was glad to be back home and let out a loud sigh of happiness that got lost in Hira Prashad’s trumpeting of our return to camp, which he always did, as if we were royalty.

he shock of the earthquake—and fear of bad luck—had tumbled away within a week and our daily routine was back in place. Indra, the mahout for Hira Prashad, and I left the stable in the heat of the afternoon to search for grass for our elephants’ evening meal. The drought had dried the grasslands and it was becoming harder to find the tender shoots our elephants liked.

Our drivers had set fires to create new growth. They do this to copy nature, which uses fire the same way to hurry things along. A

mong the charred stems, there were already bright green shoots poking up like a thin carpet. If only we would get a little rain, the carpet would thicken. But there was not a raincloud in sight. The drought had the jungle by the throat like a tiger on a deer.

Up ahead I saw a figure bending over near the edge of the forest. I squinted to see if it was one of our stable boys. The high-pitched bleating of a young animal suddenly pierced my ears. It was the sound an animal makes when caught by a leopard.

“Agat! Agat!” I shouted, urging on my tusker. But he did not need a command. Hira Prashad moved so fast we were at the edge of the forest in less than a minute. It was the fisherman’s boy from the river! On the ground in front of him were a dozen wire snares, and struggling in one of them was a spotted deer fawn, no more than two months old. It tried to stand and fell to the ground.

“What are you doing here?” I shouted at him.

“Babu, please,” he pleaded in Hindi, bowing on his knees before me and holding his hands clasped in front of him. “My family is starving. I have six younger brothers and sisters. My father has run away and left us.”

Indra jumped off our tusker to free the spotted deer fawn. I climbed down to help him. The fawn jerked about so much I was afraid she would pull her leg out of joint. Indra held her down while I freed her from the snare. The fawn would not survive the night among the jackals and leopards with an injured leg. I stroked her fur, and she started to calm. The fawn knew Indra and I, at least, meant no harm.

While our backs were turned, the boy took off running.

“Indra, I am going after him!” I shouted, and headed into the forest. I ran fast and caught sight of him. He had crashed into a dense thicket of spiny acacia vines and was caught.

“You! How could you hurt a fawn?” I shouted.

I picked up a stick and whacked at the thicket. The boy whimpered in fear and shut his eyes. I was panting and furious. I slapped the stick hard at his feet. The stick snapped from the force of my blow.

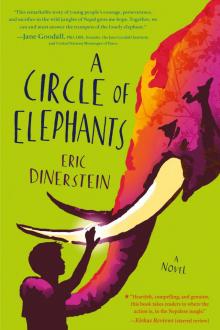

A Circle of Elephants

A Circle of Elephants